By Miguel Metelo de Seixas and Isabel Paço d’Arcos.(1)

I – THE ROYAL FLAGS OF BURGUNDY DYNASTY (12th – 14th CENTURIES)

To speak of the genesis of the national flag is to address a topic that lends itself to a mistake. The same misunderstanding and problematic that irreparably involves the ideological and temporal concept of nationality. In reality, the flags we present in the first part, essentially functioned as identifying signs for the King of Portugal – Royal Standard, and can only be assumed as national flags through a broad and somewhat retrospective approach. For the image of the nation founded in the 12th century and endowed with historical continuity (or even with a certain historical mission) the historiographic construction corresponded to another image, constructed in a mirror: that of a certain continuity of national symbols, including the flag. But this continuity exists, in fact, only as a nationalist historiographical construction, because the first flags that we will address here, we emphasize it again, are, fundamentally, identifying signs of the King (Royal Standards) and not of the Nation.

It is certain that, in medieval and modern ideology, the King, whose dynastic origin is always linked to a divine choice, incarnates and represents the group of his subjects – the people over whom he reigns. In this context, we can consider royal flags (Standard Flags) as symbols of the State itself; as for considering them as symbols of the nation, it depends strictly on knowing when we can start talking about national sentiment and when that feeling starts to be revised in the figure and consequently in the King’s flag – a complex theme in the history of mentalities, which goes beyond the scope of this text. Speaking therefore of the Standard Flags used during the first reigning dynasty in Portugal, the Burgundy House, it should be noted that no example of them has reached us, which is easily understood when we take into account the extreme difficulty in conserving such perishable materials. We know of the existence and characteristics of these flags by the references made to them in the current documentation, by the legislation that regulates their use and by the heraldic sources (starting from the hypothesis, perfectly credible, that the contents of the flags would follow the evolution of the coat of arms of the Kings of Portugal). It’s, therefore, because of all these sources, that it’s possible for us to do a reconstruction of what would be the shape and content of the flags of the Kings of the 1st dynasty.

FROM COUNT DOM HENRIQUE TO KING D. AFONSO HENRIQUES (? – 1185)

Many and pertinent doubts hang over the flag used by Count D. Henrique and his son D. Afonso, first King of Portugal. However, it seems unquestionable to believe that both have flown their own flag, at least on the battlefield, as this was the custom then in force in all Europe and in particular in Burgundy, where D. Henrique was born. However, nothing is said in current sources about the constitution of these flags. A later tradition, based in part on the heraldic allegedly used by D. Henrique, came to attribute to the Count the use of a white flag bearing a cross. This flag would point to D. Henrique’s origin and quality as a Burgundian crusader. The Iberian Reconquest, in effect, was equalled with a holy war,or crusade, against the Islamists who then dominated a substantial part of the Iberian Peninsula. As such, it would make sense for D. Henrique to display the largest symbol of the crusaders, precisely the cross with the simplest shape, and for this reason called “chã”. It would also be justified for this cross to be blue, as this color is sometimes chosen by the Crusaders of Burgundy origin. Furthermore, the choice of blue could also be linked to the fact that this is the color attributed to Our Lady, which is not small when we consider the importance that the Marian cult attained in early medieval Portuguese religiosity.

After all, did D. Henrique and his son D. Afonso I use this flag? We do not have the elements to allow us to answer this question with certainty, and until some careful research does not bring glowing discoveries, we will keep a prudent position on this issue. The absence of documentary evidence prevents us from permanently affirming the existence of this flag, however it is unquestionable that these sovereigns have made use of their own flag. In the absence of any other credible hypothesis, the white flag with the blue cross has tradition and historical credibility in its favor, eventually becoming known as the “foundation flag”.

FROM KING D. SANCHO I TO KING D. SANCHO II (1185 – 1248)

If so many doubts are raised about the flag used by the first King of Portugal and his father, on the contrary, on his immediate successor, we can have some certainties. They derive, on the one hand, from our knowledge of the contemporary vexilological uses and customs and, on the other, from the existing documentary evidence regarding the use of heraldic arms by King D. Sancho I. We know, in effect, that the coeval Christian sovereigns, and in particular that of France and those of the other peninsular kingdoms, to which D. Sancho was linked by closer ties of culture and kinship, sported square flags on which his arms were projected (as they used them, for example, in shields or stamps). Now, while we are not absolutely sure about the weapons of D. Afonso Henriques, his son D. Sancho undoubtedly used the famous silver shield with five blue inescutcheons, with the flanks pointing to the center, each shielded seeded of silver bezants. Everything points, therefore, that the royal banner (royal Standard) would consist of projecting these arms onto a square, which was the form reserved for the royal insignia (so that they were immediately distinguished, on a battlefield, from the other banners, which had shapes different according to the dignity of the people or institutions represented).

The origin of this royal banner is therefore directly related to the arms of the Kings of Portugal and, by tradition, linked to the episode of the battle of Ourique, myth of the foundation of the kingdom, justification of the reigning dynasty and of consecration of independence itself. The choice for the colors of the arms and the flag turns out to be very different from what was customary in European heraldry at that time, in which the red / silver bichromies were dominant (blue being a relatively rare color). Given the medieval sensibility, it is likely that the chromatic option has been linked to two factors: on the one hand, it may be another Marian reference, since white and blue are precisely like nuclei of the Virgin. On the other hand, it can mean the celestial origin of the arms, which the myth of Ourique presents as a donation from Christ himself to the first King of Portugal, in guarantee and demonstration of the sacred pact of the foundation of the new Christian kingdom. White and blue are, in any case, a plastic manifestation of the sacredness of the Portuguese monarchy, patented in the symbols that represent its king: the arms and the flag. These will maintain their shape until the reign of D. Afonso III, occupying, therefore, in addition to that of D. Sancho I, those of his successors D. Afonso II and D. Sancho II.

The evolution of the arms of the king (and the kingdom) will dictate, from now on, the essential modifications of the royal banner; principle that we can actually see until the final stage of the monarchy.

FROM D. AFONSO III TO D. FERNANDO I (1248 – 1383)

The royal banner underwent its first major change precisely in order to follow the evolution of royal heraldry. This was modified by D. Afonso III with the addition of a red border loaded with a variable number of or castles. What is the reason for this change?

The traditional explanation, already mentioned by the chronicler Rui de Pina, states that the castles in the bordure represent the seven fortresses conquered from the Moors by D. Afonso III (there are, of course, many differences in the identification of these seven castles), thus representing possession, from the Kingdom of the Algarve or alternatively, the castles of Riba-Coa, an area whose definitive integration into Portuguese territory dates from the reign of D. Dinis. Another explanation links the adoption of the bordure charged with castles to the wedding of D. Afonso III with D. Beatriz de Castela; this theory, however, falls apart when we know that the aforementioned border already appears on a 1251 stamp, two years before the celebration of the said marriage. Besides, D. Afonso had already in France, while Count of Bologna, a marshalled shield from a sown of castles and the weapons of his wife D. Matilde, Countess of Bologna. The use of the sowing of castles, alluding to the Castile weapons inherited from his mother (Queen D. Beatriz), reveals the importance of this genealogical connection for D. Afonso. In fact, the Castilian-Leonese monarchy enjoyed a period of splendor that was not alien to the personal reputation of Alfonso VIII of Castile, a sovereign whose brilliant matrimonial policy had allowed the House of Castela to be linked with the most important royal families in Western Europe.

Heraldic rules determine that no two people are simultaneously using the same weapons, as these serve as an identifying sign for their user. It is usual for full arms to belong exclusively to the head of a lineage, each of the remaining members of the family having to introduce in their shield any element that distinguishes them: this is called diferencing and cadency in heraldic language. The brilliance of the Castilian monarchy explains that all of Alfonso VIII’s grandchildren picked the differentiation elements for their arms from Castile’s weapons, with the obvious exception of the firstborn and sovereign D. Sancho II of Portugal and Saint Louis of France, who brought weapons of their kingdoms without any difference. The borderur of castles, originating therefore in the weapons of Castile, worked for D. Afonso III as a personal heraldic difference, being later integrated definitively in the arms of the Kingdom. it is noteworthy that the number of castles on the bordure assumed by D. Afonso was fluctuating: perhaps the bordure was originally sown with castles, then partly taking over the infant’s “French” arms; in any case, the number of castles depended on the filling of the empty spaces around the bordure, and therefore varied with the shape of the shield and the type of its physical support. The number of castles, in fact, will only be fixed at seven by habit, but not by legal provision, from the second half of the 16th century (reigns of D. João III and D. Sebastião, but above all D. Henrique) . The flag thus constituted, with the inclusion of the bordure of castles, continued throughout the following successors of D. Afonso III: D. Dinis, D. Afonso IV, D. Pedro I and D. Fernando I.

II – THE ROYAL FLAGS FROM DYNASTY OF AVIZ UNTIL THE FALL OF MONARCHY(1383 – 1910)

With the advent of the House of Avis, the royal banner not only undergoes changes, but also enters a new phase of existence, it has already the fundamental characteristics that will remain, in reality, until the fall of the monarchy in 1910. The first of these characteristics is related to the fact that we know iconographic documents that allow us to know for sure what these flags were like: from D. João I, in fact, representations of the flag abound, whether in illuminations, paintings, drawings, complete works, or other supports. The second characteristic points to the progressively national character of the royal banner: it is certain that it continues to represent, above all, the King, but one begins to differentiate the King as head of state and incarnation of the nation, from the King as a person. And there is no doubt that, from the 1383-1385 interregnum episode, one can clearly speak of Portuguese national sentiment: that national spirit can be seen in the King himself, in the arms that identify him at all times and in the flag that represents and accompanies him, on the battlefields. Finally, a third characteristic of the flags of this period is the existence of a high number of parallel uses of flags which, not representing the King or the nation, however symbolize the State in some of its branches: as well as appearing as flags of war, as navigation, as well as trade.

On the controversial question of the extent to which the royal flag represents the King or the Nation, a subject that seems to follow an evolution in everything similar to that of royal heraldry, one last word. In effect, from D. João I onwards the kings of Portugal began to use not only the weapons of the kingdom, transmitted hereditarily and ordered according to the rigid rules of the armory, but also personal signs, as a rule chosen by themselves and in which one tried to mirror the religious and moral principles, the political objectives, the personal projects of each King. These signs were called personal standards, beginning their use with D. João I and the most famous and widespread of them being the armillary sphere of King D. Manuel I. Now, we know that in the reign of D. João I, this King made use of of a personal banner with the colors, letters and figure of standard, a habit that his successors kept all, at least until King D. Sebastião. Thus the official flag of the King, symbol of the State and the Nation, was obviously differentiated from its Royal standard flag, symbol of his person. This distinction ended in the 17th century, when the so-called royal pavilion was created. The royal flag had already come to symbolize the State, if not the Nation, while standards had fallen out of favor; therefore, it was necessary to create a personal flag for the King, designed to signal his presence, both in time of war and peace. This is how the royal pavilion (royal Standard) was created, whose use is perpetuated (…). Both corporate flags and the Royal Standard pavilion are personal signs of monarchs and not of the nation (…).

FROM D. JOÃO I TO D. AFONSO V (1385 – 1481)

With the arrival of D. João I, the royal arms underwent another change, which was mirrored in the respective flag. As master of the Order of Avis, King D. João made use of the so-called weapons of ancient Portugal (that is, the inescutcheons with bezants, without bordure of castles), under which he displayed the cross of this Order to mark his condition as master of it . When he became regent and defender of the kingdom, or soon after his acclaim as king, in the courts of Coimbra, D. João I started to show the full arms of the kingdom (with the bordure of castles, therefore), but kept behind them the Avis cross. Why did D. João keep this insignia, even after having renounced his status as a Master? Perhaps the answer lies in the symbolic importance of the name Avis: it was not only D. João to be known or commonly referred to as the Master of Avis, but also to the nationalist cause he was called the cause of the Master of Avis. This even led to the new reigning branch of Royal House, becoming known as House of Avis. The cross of the Order would therefore work, together with the cross of Saint George, as a symbol of the cause of independence defended and represented by D. João I.

D. JOÃO II (1481 – 1495)

The inclusion of the cross of the order of Avis in the Royal Arms, and in the flag, lasted until the reign of D. João II. In the corts (assembly of representatives of the estates of the real) by this monarch in 1482, the question of the reform of royal arms was raised and would have given prolonged discussions, which later passed on to the royal council. Over three years, the theme of how to reform the heraldry (and, consequently, the flag) of the King of Portugal was debated in that institution; the discussions then generated were well nourished by arguments against and in favor of the proposed changes, as stated by Álvaro Lopes de Chaves, secretary of the king. What issues, then, were the debates leading to this reform? First of all, there was the question of the suppression of the cross of the Order of Avis: as the chronicler Rui de Pina points out, these had been introduced into the shield of royal weapons by mistake of those who represented them (and also for symbolic reasons, we will add); therefore, there was an urgent need to supress this element that was not part of the real order of arms. Second, it was advisable to straighten the side shields, traditionally pointed at the center; a position that, in the words of the aforementioned chronicler, “seemed to be something of a breach”, that is, it could seem an indication of some loosening of real arms. Thirdly, it was considered the possibility of including in the royal arms elements that represented the new domains that the king of Portugal had incorporated in his Crown, thanks to the efforts of the discoveries and conquests.

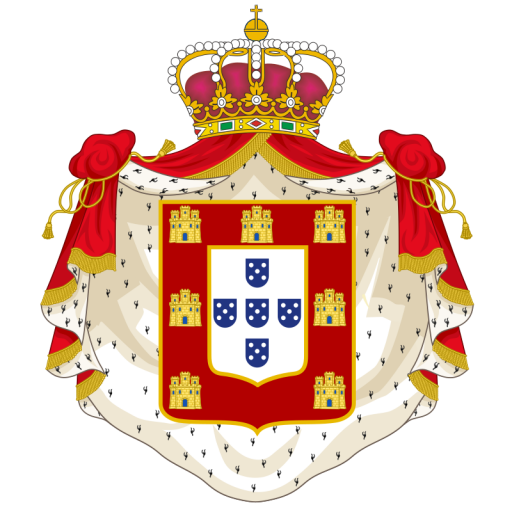

Ein 1485, when D. João II needed to mint coins, a decision was finally reached on how to order, from then on, the arms of the King of Portugal. Of the three proposals, the first two were retained: the ends of the cross of the Order of Avis were suppressed and the side inescutcheons were straightened (therefore all five were in the same position), but it was eventually understood that no symbol of overseas expansion was to be included in the arms. As for the flag used by D. João II, it consisted of projecting those same arms onto the square surface of the royal flag, as it had been done until then.

The arms thus constituted remained, with only variations of style and alterations in the elements outside the shield, throughout the rest of the monarchy’s duration (with some brief exceptions that we will deal with later) and even, in reality (…), to the present day. It is nevertheless amazing and rare to find, therefore, that the order of Portuguese national arms has remained, in essence, unchanged for half a millennium!

FROM D. MANUEL I TO D. JOÃO III (1495-1557)

The custom of the royal flag consisting on the projection of the royal coat of arms onto the square formed by the flag cloth, in force until the beginning of the reign of King Manuel I, were changed at the initiative of this monarch. Instead of the mere projection of the contents of the shield, the flag began to display a white field in the center of which was the coat of arms surmounted by the open royal crown. We could ask about the reason for this innovation and the choice of white as the background color of the flag. The fundamental cause of creating a background color for the flag, we must look for it in the need to represent more clearly the royal quality of its owner. The square shape of the flag, exclusive to the sovereign, had hitherto served as a sufficiently clear indicator to indicate the royal status. However, either because the use of square flags had in the meantime been extended (by concession or abuse) or because its meaning was no longer so clear to most observers, there was a need to add another distinction.

Os usos heráldicos dos reis de Portugal há muito incluíam a representação de ornamentos exteriores ao escudo. Desses ornamentos a coroa real aberta era a que simbolizava de forma mais nítida a condição de rei, por isso se havia tornado a sua figuração tanto em selos de autoridade como em pedras de armas, moedas, ou quaisquer outras manifestações heráldicas. Tanto assim que a representação das armas do rei de Portugal, podendo compreender ornamentos variáveis, tinha passado a representar como elementos fixos e quase indissociáveis o escudo (essência das armas) e a coroa (indicativa de que se tratava das armas de um rei). Assim, parece natural que D. Manuel I tenha querido transplantar para a bandeira esta outra distinção, indicativa de soberania: o conjunto escudo / coroa.

Mister se tornava criar uma cor de fundo, sobre a qual assentaria o referido conjunto: a escolha recaiu sobre a cor branca. Resta averiguar o porquê desta opção. Mais uma vez, a resposta é fácil de encontrar: trata-se de uma questão simbológica e estética. Era preciso que o fundo da bandeira tivesse algum tipo de correspondência simbólica com as armas, e por isso se escolheu precisamente a cor do próprio campo delas – prata ou branco. Por outro lado, essa cor devia fazer realçar o escudo, o que é assegurado pelo contraste visual do fundo branco com o vermelho da bordadura de castelos e mesmo com o amarelo da coroa.

Esta bandeira esteve em uso durante os reinados de D. Manuel I, D. João III e durante a maior parte do de D. Sebastião.

Esta bandeira esteve em uso durante os reinados de D. Manuel I, D. João III e durante a maior parte do de D. Sebastião.

FROM D. SEBASTIÃO TO D. MARIA I (1557 – 1816)

O reinado de D. Sebastião corresponde a um período importante na consolidação do poder régio e na própria reflexão acerca da origem, natureza e limites desse mesmo poder. Na esteira da tendência geral europeia, a monarquia portuguesa tende a afirmar a sua plena soberania, em conformidade com o princípio de “rex in regno suo est imperator” (“o rei no seu reino é imperador”), isto é: dentro das fronteiras do seu reino, o monarca não reconhece autoridade superior à dele, que não seja a divina (porque na doutrinação medieval como na moderna, Deus é fonte primeira e última de todo o poder). Para simbolizar essa doutrina política, os reis europeus haviam ficado a fazer uso de uma nova coroa régia. Até então, com efeito, vigoravam na Europa as chamadas coroas reais abertas, compostas por um diadema ornamentado com pedras preciosas, sobre o qual corria um friso de folhas de acanto ou outros elementos decorativos (por vezes específicos de um determinado rei, como as flores-de-lis dos reis de França e Inglaterra). Para assinalar a mudança e o engrandecimento do conceito de poder, os reis começaram a modificar a coroa, tornando-a cada vez mais próxima do modelo fornecido pela coroa imperial (do Sacro Império Romano-Germânico). Esta coroa, dita de Carlos Magno e porventura inspirada nas práticas bizantinas, conservava-se, juntamente com os restantes símbolos do poder imperial, no tesouro da catedral de Aix-la-Chapelle. Ao simples aro decorado com um friso juntava uma cobertura de aros e forro que a fechavam na parte superior, sendo o conjunto encimado por uma cruz. Essa cobertura significava, precisamente, que, para além de Deus, o Imperador não reconhecia nenhuma autoridade acima dele. Foi portanto conforme este modelo e esta prática que D. Sebastião modificou a coroa das armas reais portuguesas, fechando-a com aros rematados por uma cruz (ou, por vezes, por um globo encimado pela cruz), por forma a assinalar a sua condição imperial, ou seja, a sua plena soberania. Talvez quisesse mesmo representar ao mesmo tempo a própria existência do império político ultramarino português, exaltando desta forma o sentimento nacional que então atingia um dos seus momentos mais elevados (não esqueçamos que Luís de Camões escreveu Os Lusíadas nesta época). A coroa assim criada, chamada coroa real fechada, manter-se-á nas armas e na bandeira dos reis de Portugal até ao fim da monarquia, apenas com variações de estilo (composição do diadema e do friso, número e formato dos aros, existência ou não de forro, elementos decorativos do conjunto). Usaram-na, portanto, para ale dos restantes reis da Casa de Avis (D. Henrique e D. António), os soberanos da Casa de Habsburgo (Filipe I, II, e III) e, depois da Restauração de 1640, todos os da Casa de Bragança (começando com D. João IV e terminando com D. Manuel II). A modificação da coroa não afectou, todavia, a cor do campo da bandeira, o qual permaneceu branco. Assim, a bandeira branca tendo ao centro o escudo de armas encimado pela coroa real fechada tornou-se na bandeira nacional portuguesa vigente durante mais tempo, pois o seu uso estendeu-se por cerca de dois séculos e meio, desde o reinado de D. Sebastião até ao fim do de D. Maria I. Entretanto, em meados do século XVI, em data difícil de assinalar, a bandeira real deixou de ser quadrada, para assumir o formato rectangular. Tal modificação ter-se-á dado devido à influência das bandeiras navais, nas quais, por causa da diferença da conservação do tecido, se havia passado a preferir um formato que deixasse uma margem maior no lado flutuante da bandeira, no qual se verificava um mais rápido desgaste. O que permitia que a figura central (as armas reais, neste caso) fosse menos atingida pelo gasto. (…).

D. JOÃO VI (1816 – 1826)

As armas reais e, consequentemente, a bandeira nacional voltaram a sofrer uma nova modificação no início do reinado de D. João VI, em circunstâncias que explicaremos de seguida. Por motivos estratégicos, a Família Real, a Corte e os organismos centrais do Estado haviam-se transferido para o Brasil em 1808, escapando desta forma às garras dos invasores franceses. Há muito tempo que o Brasil constituía o coração económico do império português; a partir daquele momento, tornou-se também no seu centro político. Para manifestar essa nova condição, o Rei D. João VI, chegado ao trono em 1816 depois de uma longa regência durante a incapacidade de sua mãe, D. Maria I, houve por bem alterar a designação oficial do reino. D. Manuel I havia inaugurado um título régio extenso e bem denotativo da dimensão do império que os portugueses haviam criado mundo afora: Rei de Portugal e dos Algarves daquém e dalém mar, em África Senhor da Guiné e da conquista, navegação e comércio da Etiópia, Arábia, Pérsia e da Índia, etc. Nesse longo título, como se vê, não constava menção ao Brasil, e por essa ausência contrastar violentamente com a realidade política entretanto criada, determinou D. João VI a elevação do Brasil a reino. Formou-se então uma Monarquia tríplice, denominada Reino Unido de Portugal, Brasil e Algarves, cujas armas consistiam na alegada junção da heráldica dos três Reinos: Portugal fornecia o núcleo central com o campo de prata e as quinas; o Algarve contribuía com a bordadura de castelos, tradicionalmente associada, como vimos, à integração deste reino sob D. Afonso III; mas o Brasil, esse, como poderia estar simbolizado ? Pois se, até então não tinha categoria de reino, nem armas próprias que o representassem ! Resolveu-se a questão de forma expedita: a lei de 13 de Maio de 1816 dotou o novo reino de armas próprias, consistindo num campo de azul com uma esfera armilar de ouro. A escolha deste símbolo explica-se facilmente; a esfera armilar, empresa dos reis D. Manuel e D. João III, havia sido largamente usada nos domínios ultramarinos, ao ponto de ter servido, desde finais do século XVII, como elemento identificativo do estado do Brasil (nas moedas emitidas nas oficinas monetárias portuguesas no Brasil, por exemplo). Nada mais natural, portanto, que a retoma deste símbolo de uso já consagrado para com ele se ornar a heráldica do reino do Brasil. As armas do Brasil assim constituídas passaram a ser usadas em conjunto com as de Portugal: ao escudo com essas armas, de formato redondo, foi sobreposto o das armas reais portuguesas. O conjunto assim criado passou a constituir a heráldica do Reino Unido de Portugal, Brasil e Algarves. É interessante notar que nesta composição as armas reais portuguesas parecem ser sustentadas pelas brasileiras, tal como o Brasil estava servindo de sustentáculo do império português, no momento a aflição pelo qual Portugal passava com as invasões francesas.

A bandeira dotada das armas deste Reino Unido manteve-se em vigor em Portugal até à morte do Imperador-Rei D. João VI em 1826. O falecimento deste soberano veio despertar delicadas questões de ordem política e dinástica, as quais se reflectiram de forma marcante na bandeira nacional.

FROM D. MARIA II TO D. MANUEL II (1830 – 1910)

O término do reinado de D. João VI correspondeu a uma época conturbada da história portuguesa, durante a qual, ao longo de oito anos (1826 – 1834), se defrontaram os legitimistas (partidários de D. Miguel) e os liberais (seguidores de D. Pedro e de sua filha D. Maria II). Foi esta penosa guerra civil que originou nova mudança na bandeira nacional. A segunda metade do século XVIII tinha assistido à difusão da moda do uso de laços e topes, apostos em vestes e chapéus que indicavam a ligação a um determinado Estado, ou a um movimento ou ideário político. Nesse sentido, já em 1796 o príncipe-regente D. João (futuro D. João VI) havia instituído um laço escarlate e azul para os chapéus de todos os militares ao serviço de Portugal. Após a revolução liberal de 1820, surgiu a ânsia de criar novas cores nacionais. Na reunião das Cortes Extraordinárias e Constituintes da Nação Portuguesa de 14 de Agosto de 1821, o deputado Manuel Gonçalves de Miranda propôs, assim, a criação de um “laço nacional” das cores verde e amarela. As Cortes apreciaram a ideia, mas não as cores propostas. Em lugar destas, por proposta do deputado Francisco Manuel Trigoso de Aragão Mourato, foi decretado a 22 do mesmo mês que o laço a ser usado obrigatoriamente por todos os funcionários públicos, tanto civis como militares, e livremente por todos os restantes cidadãos, teria as cores branco e azul. Essa escolha fundamentou-se na suposta origem das armas nacionais na cruz azul sobre fundo branco usada pelo Conde D. Henrique, pai do primeiro Rei de Portugal. A partir de então, o laço branco e azul transformou-se na insígnia de todos quantos defendiam os ideais liberais e o projecto de uma monarquia constitucional. Naturalmente assim que as forças contra-revolucionárias retomaram o poder, a seguir à vila-francada de 1823, aboliram o laço branco e azul e restauraram o azul e escarlate, por carta de lei de 19 de Junho desse ano. No movimentado período do final do reinado de D. João VI (1823 – 1826), da regência de D. Isabel Maria (1826 – 1828) e do reinado de D. Miguel (1828 – 1834), à rivalidade entre absolutistas e liberais correspondeu a fidelidade, respectivamente, às cores azul / escarlate e branco / azul. No período da guerra civil surgiram as primeiras bandeiras azuis e brancas como símbolo da luta pela causa liberal. Essa associação tornou-se oficial pelo decreto nº 100, de 18 de Outubro de 1830, pelo qual o Duque da Terceira, regente em nome da rainha D. Maria II, criou a nova bandeira nacional “bipartida verticalmente em branco e azul, ficando o azul junto da haste, e as Armas Reaes collocadas no centro da Bandeira metade sobre cada huma das cores”. Com a vitória da causa liberal, consagrada pela convenção de Évora-Monte em 1834, a bandeira azul e branca tornou-se na bandeira representativa da monarquia constitucional, e como tal perduraria vigente até à queda do regime monárquico em 1910. Vigorou esta bandeira, portanto, durante os reinados dos descendentes de D. Pedro IV que chegaram a ocupar o trono português: D. Maria II, D. Pedro V, D. Luís, D. Carlos e D. Manuel II.

(1) Bandeiras de Portugal, Lisboa, Junta de Freguesia de Santa Maria de Belém, 2004